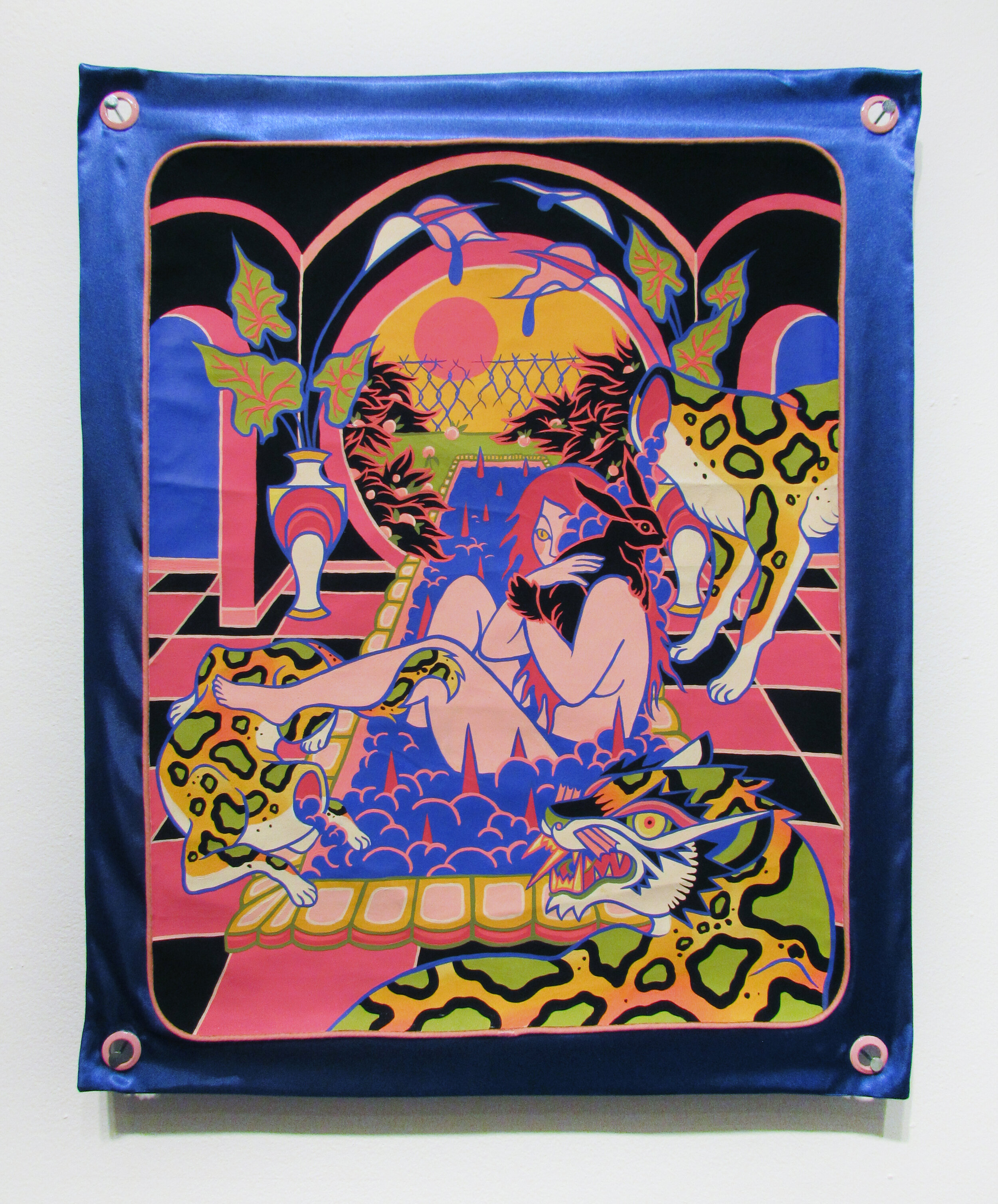

Step into the Water and You Remember Everything, 2020

In Step into the Water and You Remember Everything, Kam and Power investigate themes of fantasy and escape through the framework of queer folk art. The artists seek to preserve the ritual of creating and collecting artifact and animal icons as sentimental figures. Queer folk art is a record of our time that provides a way to speculate alternative futures. In this context, Kam and Power establish a myth reflecting reality by creating fantasy spaces of an imagined past. These spaces are escape for our inner child while also holding answers to possible futures, but only if we are brave enough to go on the quest. In this myth, we are accompanied by animals; often we are the animals ourselves.

From the Zine: Making surrealist fantasy paintings in the contemporary landscape

Like many young artists who like to draw, we became artists because there is cool looking stuff we love to draw. The irony is that we both went to an art school that places heavy emphasis on conceptualism.

Our work is a response to contemporary art that demands us to be present with the environment created by the material. It isn’t that we loathe the installation that rely on the trick of light to create wonder, nor do we reject the painting that asks itself existential questions— we just want to ask questions that don’t require us to be here. That’s because the answers don’t seem to be here. Not yet.

We aren’t always conscious of the things we paint. There isn’t a big narrative we are trying to impart. Our paintings are snippets of our lives turned into fantasy spaces. They contain past memories, present emotions, and future hopes. What we wish to impart is the freedom to imagine.

The following excerpt from Ursula K. Le Guin’s Cheek by Jowl helped us make sense of the work we made for Step into the Water and You Remember Everything.

“The monstrous homogenization of our world has now almost destroyed the map, any map, by making every place on it exactly like every other place, and leaving no blanks. No unknown lands. A hamburger joint and a coffee shop in every block, repeated forever. No Others; nothing unfamiliar. As in the Mandelbrot fractal set, the enormously large and the infinitesimally small are exactly the same, and the same leads always to the same again; there is no other; there is no escape, because there is nowhere else.

In reinventing the world of intense, unreproducible, local knowledge, seemingly by a denial or evasion of current reality, fantasists are perhaps trying to assert and explore a larger reality than we now allow ourselves. They are trying to restore the sense— to regain the knowledge— that there is somewhere else, anywhere else, where other people may live another kind of life.

The literature of imagination, even when tragic, is reassuring, not necessarily in the sense of offering nostalgic comfort, but because it offers a world large enough to contain alternatives and therefore offers hope.

The fractal world of endless repetition is appallingly fragile. There is no illusion, even, of safety in it; a human construct, it can be entirely destroyed at any moment by human agency. It is the world of the neutron bomb, the terrorist, and the next plague. It is Man studying Man alone. It is the reality trap. Is it any wonder that people want to look somewhere else? But there is no somewhere else, except in what is not human— and in our imagination.“